It’s California in the ‘60s. Neon lights and billboards decorate the Sunset Strip while the Beatles, Beach Boys, and Byrds ring out from car radios, cutting through the Los Angeles traffic. A young, rebellious generation parades through the streets as glowing marquees announce the bands at happening clubs like the Whisky a Go Go. It’s the centre of the universe for the counterculture, and the place to become a star.

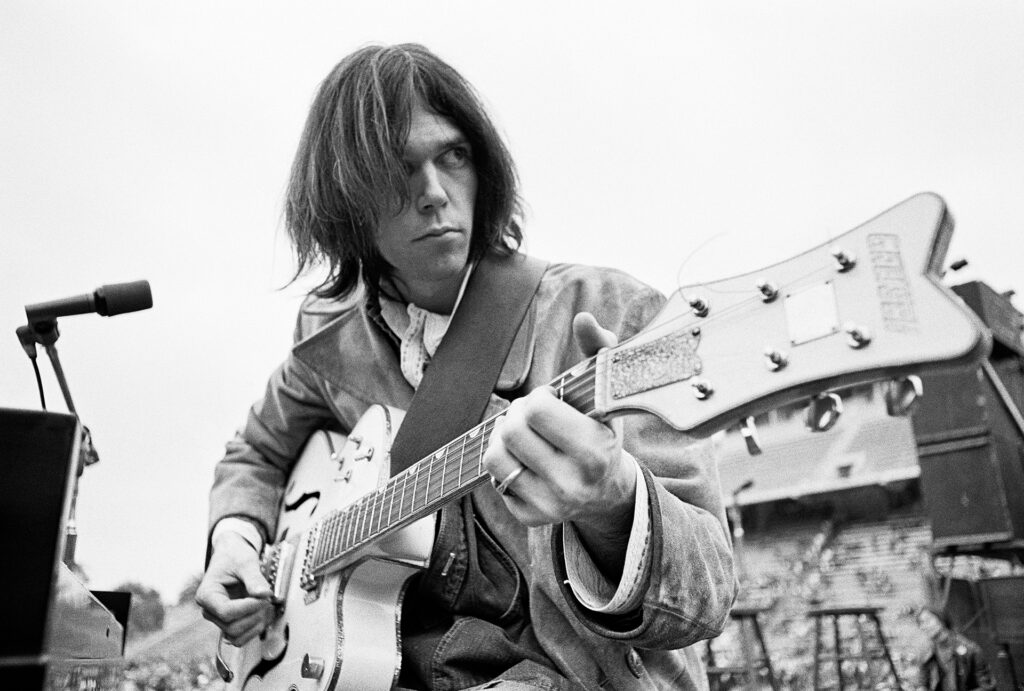

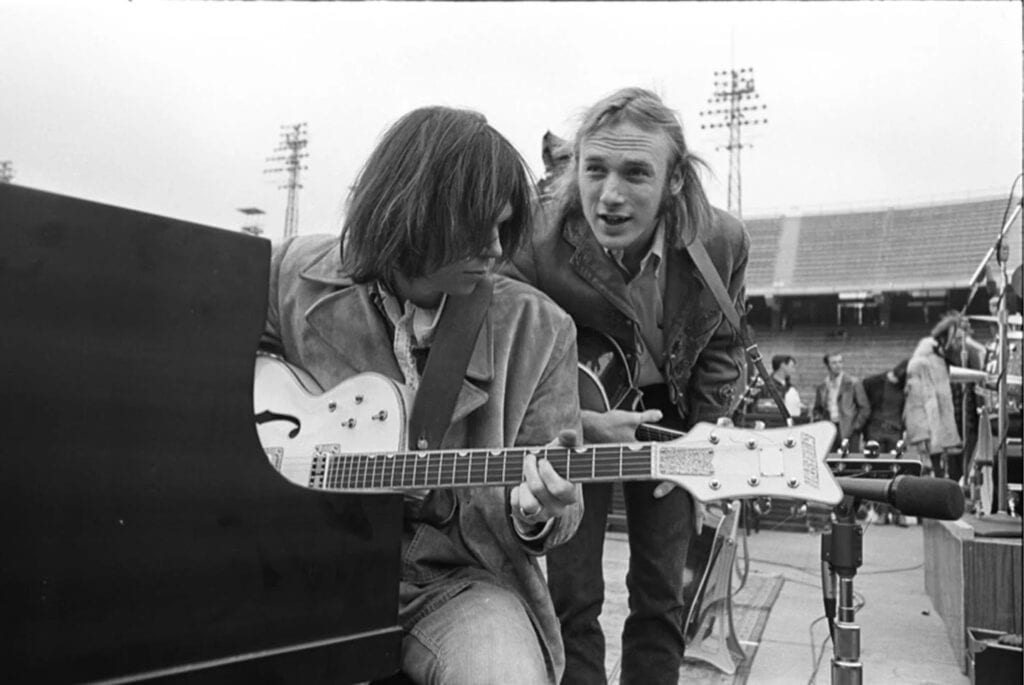

On April 6, 1966, a rush hour traffic jam on Sunset Boulevard would forever change popular music. A black ’53 Pontiac hearse, driven by Neil Young with fellow Canadian Bruce Palmer, was heading out of L.A. They had just arrived a few days earlier, searching for American musician Stephen Stills without any luck.

“We couldn’t find Stills anywhere. Eventually we gave up on L.A. and decided to head north to San Francisco, where Flower Power was in full bloom,” Young recalled in his memoir, Waging Heavy Peace.

Just as they were leaving town, they passed a white van going the opposite direction. Stills and Richie Furay were in that van and instantly recognized the hearse with Ontario plates.

“We heard a voice shout, ‘Hey, Neil!!! Is that you?’ I looked around out the driver’s window of the hearse. It was Stills!” wrote Young. “We got out and hugged right there on Sunset Boulevard in the middle of traffic. Horns were honking! To us it seemed like everybody was celebrating! Something was happening, but we didn’t know what it was.”

What it was soon became clear — it was Buffalo Springfield.

The origins of that pivotal moment can be traced back a few years to Canada, where Young developed his sound playing with the Squires throughout Manitoba and Ontario.

“He was a unique character in the Winnipeg music scene,” says John Einarson, acclaimed musicologist and author of Neil Young: Don’t Be Denied — The Canadian Years. “Neil loved folk music, he loved the lyrical sense of folk music and telling a story, but he also loved rock ‘n’ roll.”

The folk boom unfolded in parallel with the rise of rock ’n’ roll — folk brought lyrical depth, while early rock was viewed as fun and rebellious. They occupied distinct cultural spaces with divided audiences, but Young was into both.

Having tapped out the Winnipeg market, Young thought the Squires would have better luck getting gigs in Fort William, Ont. (now Thunder Bay) and drove the band out there in an old hearse named Mort.

“He starts playing the folk songs he knew … but putting them to an electric beat and an electric instrumentation. And that was kind of his version of folk-rock, even before the term folk-rock was popularized by the Byrds in the summer of ’65,” says Einarson.

Fort William is also where Young and Stills first met — when the Squires opened for Stills’ folk group, The Company. That encounter sparked a magnetic cross-border connection that would become one of the most influential collaborations in music history.

A few months later when the Squires broke up, Young gave Toronto’s music scene a shot, searched for Stills in New York, met Furay and taught him “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing,” and briefly joined Palmer in R&B-rock group The Mynah Birds — which quickly fell apart. Young was at a crossroads.

“At the time, there really wasn’t a national Canadian music industry,” says Einarson. “We had a localized, regional music scene, and Neil wanted something more than that.”

Young recognized that Canada’s audience wasn’t yet big enough to support his ambition, and the new sounds coming out of California resonated with the music he wanted to make.

“I was in Toronto, in the middle of the night, sitting in a funky after-hours dive called the Cellar,” Young wrote in his memoir. “Bruce and I were just sitting there, probably pretty stoned, and I asked Bruce if he wanted to go down to L.A.”

They sold the leftover equipment from the Mynah Birds, bought another hearse, and embarked on the historic Los Angeles road trip that would lead to Buffalo Springfield.

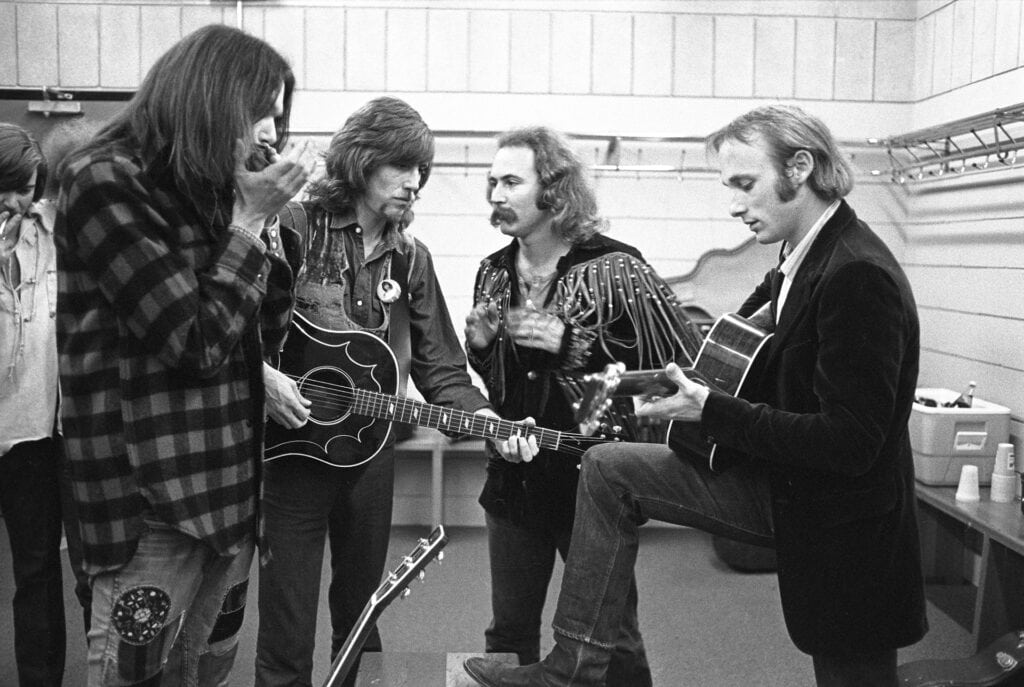

Leaving the New York music scene for the West Coast, the vocal group made waves with their four-part harmonies and sun-soaked blend of folk and pop, putting their own twist on the ‘60s California sound that had inspired their pilgrimage to the new music mecca.

As record labels shifted their focus to L.A., the city became a magnet for artists from across the U.S., Canada, and even England — breaking down boundaries and fostering new collaborations.

“It was where music was happening,” says Einarson. “It’s fascinating that they were drawn to that music scene and drawn to that location, and drawn to live amongst each other and make music together.”

Henry Diltz — folk musician turned photographer — came to L.A. in 1963 with his group the Modern Folk Quartet. They were regular performers at the Troubadour during the height of the folk revival — until one moment in 1964 changed everything.

“When the Beatles played Ed Sullivan, all of the folk groups watched that,” says Diltz. “And we immediately went out, and we electrified our instruments because that was the new thing, that was so exciting. And they were singing their own songs.”

With those ingredients — electric instruments and original songwriting — bands everywhere began to reinvent themselves. The Byrds took Bob Dylan’s folk tune “Mr. Tambourine Man,” gave it an electrified rock pulse, and hit the radio waves with a fresh new sound.

Aspiring folk-rockers followed that sound all the way to Southern California — specifically, to Laurel Canyon.

Tucked in the Hollywood Hills above Sunset Boulevard, Laurel Canyon is a steep, wooded canyon made up of narrow, twisting roads lined with treehouse-like cabins and hillside bungalows hidden among the sycamores and sagebrush.

“I immediately moved up to Laurel Canyon because that’s where all the musicians lived,says Diltz. “Before it had been actors, and then in the ’60s it became musicians.”

After playing the stages on the Sunset Strip, they could slip away from that “carnival midway” scene and, within minutes, be in their own little place “out in the country.”

“It’s really curvy hills. There are no lawns. There are no sidewalks,” says Diltz. “People aren’t walking around really, but it’s what happens inside each of those bungalows.”

It was an affordable place to live and a bohemian sanctuary for musicians. People left their doors unlocked, and guests would show up unannounced, a guitar in one hand and a joint in the other, ready to catch the inspiration that seemed to hang in the air.

“If you’re a songwriter or a singer, you drive up the hill and now you’re sort of perched above it all. And I think, it’s my philosophy or my theory, that it kind of helps to write songs about life when you’re up the hill, just above it all,” says Diltz.

Prior to this period, mainstream music wasn’t usually written by the performer. There were singers and there were songwriters. But musicians like Young, Mitchell, and others in the Laurel Canyon scene ventured to do both.

“They started writing their own songs, which is very interesting. So that’s what made it a renaissance, the dawning of the singer-songwriter making their own poems, their own music,” says Diltz.

Buffalo Springfield stood out as a band whose repertoire was made up entirely of original songs set to folk-rock instrumentation.

“The Byrds weren’t doing all original material. But here’s the Buffalo Springfield releasing their debut album, and it’s all original material. It was seven songs by Stills and five songs by Neil,” says Einarson.

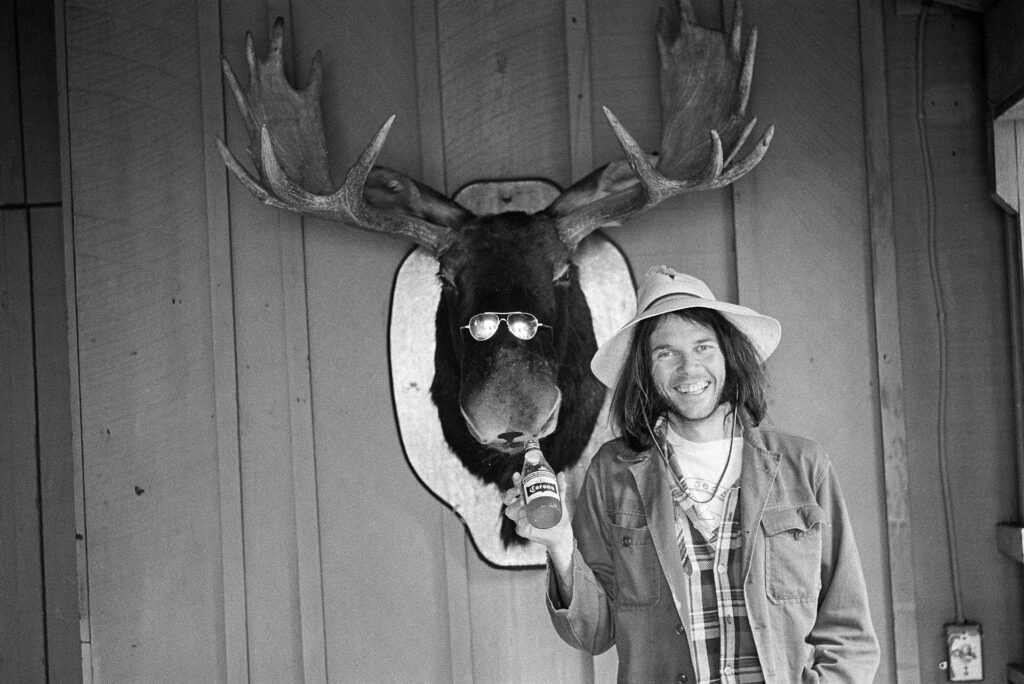

Diltz put down his banjo and picked up the “funky little camera” he found at a secondhand store. With his fly-on-the-wall approach to taking photos of his friends, he proceeded to document one of the most important eras of music history — and it started as a happy accident.

One day soon after he got his camera, Stills invited him to a folk club in Redondo Beach.

“I was photographing a huge mural that was on the wall of the club, a great big pink mural of a guy riding a bicycle and I was just focusing on it, thinking, ‘Oh, this will be interesting.’ I always look for colourful things to show in my slideshows.

“The back door opens and the Buffalo Springfield comes walking out. I said, ‘Hey, you guys, would you just stand in front of that wall for a minute? I want to show how big that mural is.’ I needed people in my photograph.

“They started making faces and doing funny things. And I got some good shots. One roll of film of them standing there. Apparently they told a music magazine that I photographed them, because I got a call a few days later. They said ‘We hear you have a picture of the Buffalo Springfield. We’d like to run it in our magazine and we’ll pay you $100.’ And I almost fell down.”

Before they helped kick off Diltz’s photography career, the five musicians of Buffalo Springfield had recently arrived in L.A. from different parts of North America and varying musical backgrounds.

Young is both “the folk guy” as well as “the screaming rock ‘n’ roll guy,” says Einarson. The Ontario-born drummer, Dewey Martin, “had played country music in Nashville. He backed up Patsy Cline and Faron Young.” Palmer, the bass player, “had played in a rhythm and blues band in Toronto.”

All of these influences came together in a brief yet powerful lightning strike, forming one of folk-rock’s seminal bands.

“When you consider the incredible talent that this band had, it’s no wonder they imploded within about 18 months, because it was just too much talent and too many egos,” says Einarson.

Young would forge ahead with an impressive solo career, which Einarson describes as “careening across a landscape of all sorts of different styles and sounds” — plus a stint in the era-defining Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

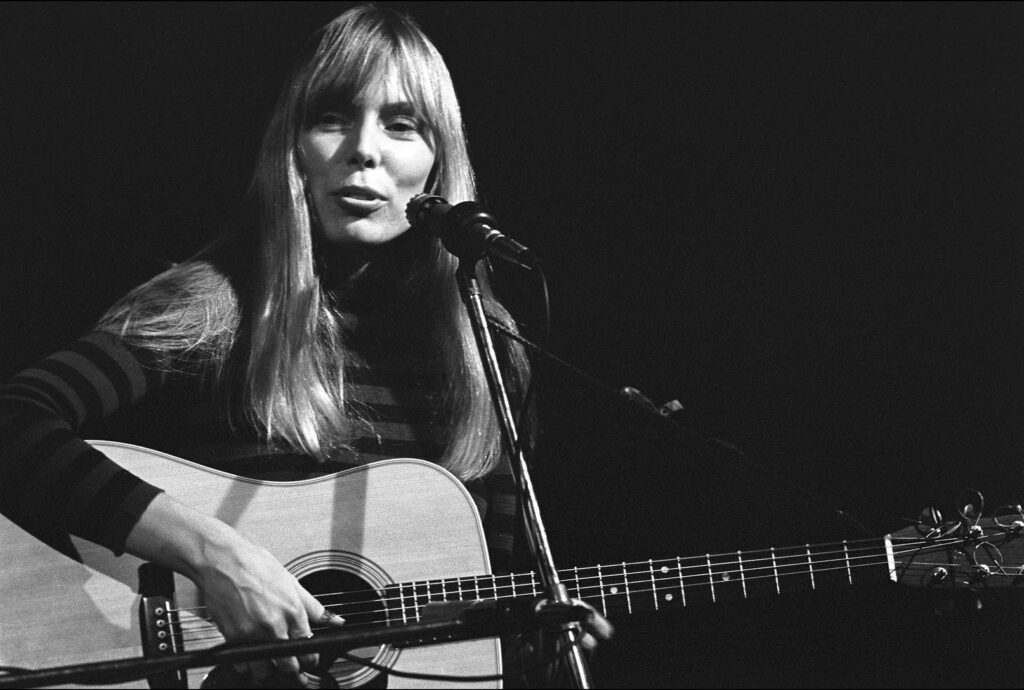

It was Crosby who brought Joni Mitchell to one of her first Laurel Canyon gatherings, where she proved herself as a force to be reckoned with.

“Mama Cass met Eric Clapton, and he was kind of shy and he didn’t really know anyone in town. And she said, ‘Oh, come up to my house, man. We’ll have a little barbecue in the backyard,” says Diltz.

“David brought Joni Mitchell. Her first album wasn’t even out yet, and we sat on the grass there, and Joni played her entire first album, just with an acoustic guitar, sitting there under some birch trees. It was magical and mesmerizing.

“Eric Clapton sat there, just astonished, just watching her fingers play, because she tunes her guitar to a chord, most of her songs have different tunings. I think he was quite amazed. I mean, he was just gobsmacked. He sat there for 45 minutes just staring at her fingers.”

Born in Alberta and raised in Saskatchewan, Mitchell emerged on the folk circuit, carrying her songs from Canada to coffeehouses across the U.S. She arrived in California with a catalogue of original compositions that other artists were already starting to record.

In L.A., Mitchell made her first albums and reclaimed her songs as her own — songs which have endured the test of time six decades later.

“To see Joni Mitchell sing her own feelings from her own heart and her own mind, about her views of life and love, that’s very special,” says Diltz.

Mitchell bought her house in Laurel Canyon with the royalties from her debut album, Song to a Seagull, in 1968. The wood-sided bungalow was immortalized in Nash’s song “Our House,” capturing a moment in time when they lived there together, but that relationship gave way to Mitchell’s independence and ambition. A true “woman of heart and mind,” she was about to shake up the music business.

Her house stands on Lookout Mountain Avenue — a vein of the canyon where Diltz, Doherty, and Mitchell’s manager Elliot Roberts also lived. In 1967, Roberts formed Lookout Management, signing Mitchell and Young as its first artists.

Mitchell would later form her own publishing company, a move towards protecting artists’ rights to their songwriting.

“You begin to see that when the music scene moved from New York to here, really at the heart of it was Elliot and David and I. And the things that they did different came out of my stubbornness. Like, we got into artists’ self-publishing,” Mitchell said in an interview with Malka Marom, Canadian journalist and author of In Her Own Words.

As a songwriter, Mitchell pioneered an introspective approach, writing about her own feelings, experiences, and observations. Her 1971 album Blue is a strong example.

“No one else, no other female singer, was singing that directly at the time,” says Einarson.

Just as Mitchell famously captured the spirit of Woodstock in song, her early music paints a layered portrait of life in Laurel Canyon — through her eyes, and literally through her window on Ladies of the Canyon, where she bore witness to the canyon scene. The story of that time and place would be incomplete without the colours she added.

“Like Paris was to the Impressionists and the post-Impressionists, L.A. was the hotbed of all musical activity. The greatest musicians in the world either live here or pass through here regularly. I think that a lot of beautiful music came from it, and a lot of beautiful times came through that mutual understanding. A lot of pain came from it too, because inevitably different relationships broke up and it gets complicated,” Mitchell said in her interview with Marom.

“It was a time. It was a renaissance. It was a flowering of new musical ideas,” says Diltz, remembering the time fondly and simply as “Peace and love.”

The counterculture that surrounded the music was defined by a generation determined to break the mold and explore new paths — something that Young, Mitchell, and their peers did wholeheartedly.

“That was all before music became a business, an industry, a commodity, or an asset for any of us. Music was more important than ‘making it,’” Young wrote in his memoir. “It was so cool, with everyone sitting in a big circle talking and sharing songs together or playing solo. Music was our language.”

Times changed, and the L.A. music landscape continued to evolve. But even if we can’t go “back to the garden,” those early years — and the music that resulted — built a permanent foundation that redefined popular culture, shaped the trajectory of music, and still echoes today.

When reflecting on his Canadian friends, Diltz says: “People come down from Canada, and they seem like such nice, friendly, interesting people. And I’m wondering if maybe it’s because of the lifestyle. It seems more natural.”

Einarson emphasizes the impact of these artists above the border in Canada, even while they were making music history down in L.A.

“To discover that there were Canadians involved in early rock ‘n’ roll, I was always so jazzed, so excited,” he says. “That you had Canadians at the forefront of all of that, to me, it’s always made me feel very proud.”

John Einarson is an acclaimed musicologist, broadcaster, and educator from Winnipeg. He is the award-winning author of more than 20 music biographies. Einarson will be featured as a panelist at Echoes Across the Border: Laurel Canyon and the Northern Connection in Calgary on October 4, 2025.

Henry Diltz is a music photographer who has shot more than 250 album covers and thousands of publicity shots in the ’60s and ’70s. He was also the official Woodstock photographer. For information on hand-signed fine art prints and special events, visit henrydiltz.com.