You may or may not know the name Jack Richardson (aka ‘Jack the Bear’ or ‘The Round Mound of Sound’), but you’ve probably heard one of the iconic hits that he produced: “These Eyes” and “American Woman” by the Guess Who, “Night Moves” by Bob Seger or Alice Cooper’s “I’m Eighteen,” to name a few.

Behind so many rock ‘n’ roll chart-toppers throughout the 1960s and ‘70s, along with helping to establish Canadian content regulations and CIRPA (The Canadian Independent Record Producers Association), the late record producer, who passed away in 2011, was appropriately nicknamed ‘The Godfather of the Canadian Music Industry.’

Working with, and advising, some of the biggest acts in the world, Jack became known as one of the best record producers of his time, producing over 240 albums, among them 38 gold and platinum records.

Though he was recognized as a producer, he always remained a musician to the core. Playing bass in a big band called the Westernaires, and Bobby Gimby’s orchestra throughout the 1940s, Jack’s early years as a professional musician would later contribute to his impeccable timing as a producer, and ability to play and teach almost any instrument.

Later, as an account executive at advertising agency McCann-Erickson in the mid-‘60s, Jack realized the potential of pairing soft drink commercials with popular Canadian rock ‘n’ roll acts, and spearheaded many successful campaigns for Coca-Cola Ltd. using acts, such as Bobby Curtola, David Clayton-Thomas, Jack London, and the Guess Who, along with American artists Stevie Wonder, and the Supremes.

By 1968, he had founded Nimbus 9 Productions, along with three business partners, and signed the company’s first act, an up-and-coming band from Winnipeg called the Guess Who, whom he’d previously worked with producing Coke ads.

“He mortgaged his house to make that first Guess Who record,” says Bruce Carter, a London documentarian that produced the 2002 film Adventures in Rock, which told the story of Jack’s influence on the Canadian music industry. “He put everything on the line. He was 41 or 42 with five kids, and he mortgaged the house! Shirley, his wife, agreed and felt he could do it. He really rolled the dice. Low and behold, ‘These Eyes’ became a No. 1 smash hit.”

Nimbus 9’s Soundstage Recording Studio was built in 1972, drawing both domestic and international artists to record in Canada. Several years later, the company’s direct-to-disc label, Umbrella Records, was launched, followed by the release of albums from Toronto new wave act Rough Trade, and JUNO Award-winning jazz ensemble The Boss Brass.

“(Jack) just wanted to keep everything in Canada,” says Jack’s son, Garth Richardson, about the formation of Nimbus 9. “He had lots of offers to go down to the States and work, but he wanted to stay here.”

“Jack was so proud of being Canadian,” says Bruce. “Everyone said he would have been a multi-millionaire if he stayed in California or Chicago, but he chose to do things in Canada.”

Jack speaks about the establishment of Nimbus 9 and the making of Bob Seger’s Night Moves in a 2008 interview.

As one of the key supporters in the formation of Canadian content regulations, along with Cancon pioneer Stan Klees, Jack was involved in many aspects of the music business, helping to ensure that Canada’s recording artists and producers were given a fair shot to make records and get airplay at home, rather than having to go south of the border.

During the filming of 2002’s Adventures in Rock, Bruce says that numerous music industry veterans in Canada and beyond expressed their respect and appreciation for Jack—among them Timothy Schmidt of Poco, for whom Jack produced three records.

“At the end of the interview, he literally started to cry,” Bruce recalls. “Timothy told me that Jack was the only guy who was ever honest with him, and that he learned so much about how to play music best through Jack.”

1971’s “Just For Me and You” by Poco.

Having acted as a sounding board for so many influential people, including producer Jack Douglas during the making of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s 1980 album Double Fantasy, Jack rarely mentioned many of his most exciting musical encounters. (That album would go on to win a Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1981, BTW.)

“When we went down to California with the family, I went and hung out with my dad, while my family went down to the beach,” Garth remembers. “He said ‘Go out and sit in the lobby now,’ so I went out there. And coming down these spiral stairs is the ‘King,’ Mr. Elvis Presley…You never knew who was gonna show up. He’d hang out with Johnny Winters and Wolfman Jack, but he never really talked about it. They were just normal people to my dad.”

The producer is also credited for mentoring fellow big name Canadian producers David Foster (Céline Dion, Michael Bublé, Whitney Houston, Rod Stewart), and Bob Ezrin (Alice Cooper, Lou Reed, KISS, Peter Gabriel, Pink Floyd) before they became huge stars in their own right.

Whether it was a fellow producer, engineer or a musician that he was recording, Jack seemed to always be guiding someone.

Fittingly, Jack took a teaching position at Fanshawe College in London in 1995, working as an audio production instructor for the Music Industry Arts program. It was a position that he loved, and a program that he helped to transform. He worked well into his 70s, both teaching and producing music until his retirement in the mid-2000s.

Indeed, he influenced a countless number of established and emerging artists during his career, including his own son, Garth, who, today, is also a respected producer and engineer that has worked on albums by Rage Against the Machine and the Melvins, and also runs his own studio and recording school out of Vancouver.

Garth Richardson is keeping his father’s legacy alive through his own production and engineering work, and his recording school.

Nimbus School of Recording Arts, named after his father’s original studio, was co-founded by Garth and Bob Ezrin, and carries on Jack’s legacy and love for music production. As Garth notes, Nimbus was started to pass on the lessons that Jack taught Bob, and in turn Bob taught him.

Garth started working at the original Nimbus 9 as a teenager, getting his first engineering credit at the age of 15 on Bob Seger’s Night Moves.

“I would go to high school and sleep, and then I would go down to my job, cleaning Nimbus 9,” says Garth. “I got to hang out and watch the first Peter Gabriel record being made. I met the Bay City Rollers—they came to our house. I met Mark Farner, Tim Curry, Alice Cooper—all of the greats. I would just go and clean the toilets, then go watch bands and hang.”

Peter Gabriel’s debut 1977 solo album was produced by Bob Ezrin at Nimbus 9, the production company that Jack co-founded.

Sharing the same birthday as his father, Garth says that he inherited many of his father’s diehard traits when it comes to music-making; Garth is the only member of the Richardson family that still works in the industry.

“The one thing that I can say that my father taught me was drive,” says Garth. “My wife hates it, because I am a bull and he was a bull, too.”

Often spending more time at work than he did at home, Garth says of his father’s extreme work ethic: “There was one point where he had only been home twice in 18 months. My mother raised five kids and finally got angry. She went down to his office and said ‘You have got to do something,’ so Nimbus 9 took out a full page ad in Billboard magazine. The whole page said: ‘Jack, come home. Signed Shirl.’ He worked very hard.”

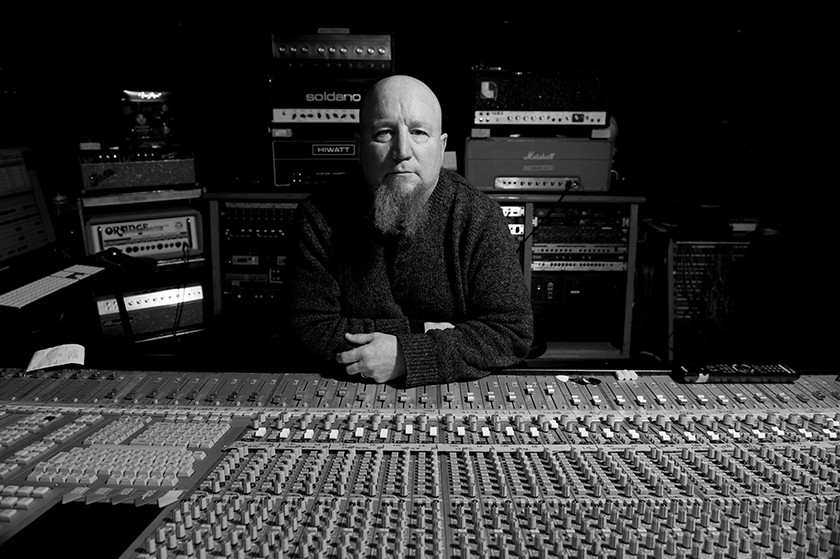

Jack with his son Garth, who is also a well-known producer and engineer.

Two generations of father and son music-makers (From left to right: Garth Richardson, Bob Ezrin, Jack Richardson, and Calvin Ezrin) Fun fact: Jack took over bass duties from Calvin when he decided to leave Bobby Gimby’s orchestra to become a doctor.

Despite his many achievements, Bruce says that Jack’s impact was largely unknown to the rest of Canada before the release of his documentary. After the film was aired in 2002, the world-renowned producer started to get some attention at home—accolades he seemingly never wanted, but certainly always deserved.

“The next morning after the documentary aired, Jack went to M&M Meats and people started talking to him,” says Bruce. “His neighbours had no idea who he was.”

That same year, the JUNO Award for Producer of the Year was named after Jack and continues to honour his legacy today. The following year, in 2003, he was inducted into the Order of Canada.

“It embarrassed people, because he never got his due,” says Bruce. “Jack is the roots of Canadian music.”

Jack passed away in 2011 at the age of 81. The night that he died, Burton Cummings, who was in London doing a concert, dedicated the evening to him.

At the funeral earlier that day, 1,500 people turned up to show their respects, among them Bob Ezrin, who did the eulogy.

“Jack would have liked it,” says Bruce. “It was a celebration.”

– Julijana Capone