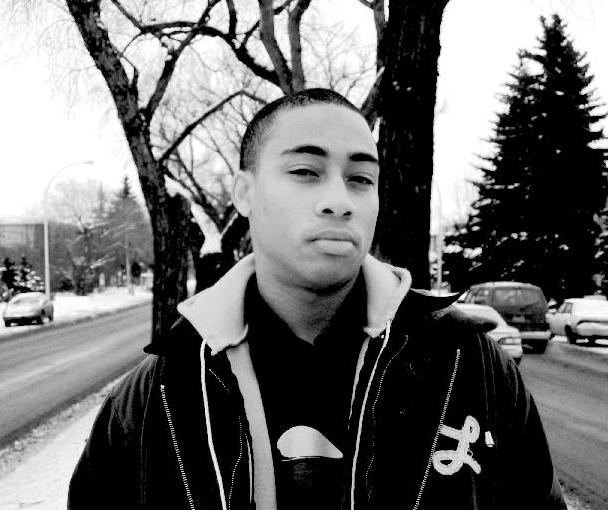

Roland “Rollie” Pemberton, better known as Cadence Weapon, has always seemed to operate on a wavelength slightly ahead of his peers. The Edmonton-born rapper released his debut album, Breaking Kayfabe, in 2005, and now, 20 years later, the record feels less like a relic and more like a blueprint for a strain of Canadian hip-hop that continues to ripple outward.

At the time, Pemberton was just 20, fresh out of high school, and briefly enrolled in journalism school in Virginia, when he dropped out to focus on music. He was an artist shaped by an unusually musical upbringing: his father, Teddy Pemberton, was a pioneering DJ on Edmonton’s CJSR-FM, running a long-standing program called The Black Experience in Sound, while his mother played piano and his uncle and grandfather were musicians in their own right.

“I grew up in basically a library of music,” Pemberton tells NMC Amplify via Zoom, his voice carrying the kind of clarity that only comes with looking back. “I just grew up with rap music around me. My uncle was a jazz, funk musician.” Music, in that household, wasn’t just entertainment; it was a way of parsing the world.

Cadence Weapon’s name itself emerged from this formative period. It was a name that captured both the personal and the combative: he was young, ambitious, and determined to stake out his own terrain within a genre still largely defined by American sounds.

Growing up Black in Edmonton came with its challenges, particularly in a city that, at the time, offered limited exposure to diverse musical forms and limited appreciation for hip-hop. “There weren’t a lot of other Black kids in school,” he says. “There wasn’t a lot of appreciation for hip-hop. My dad was one of the first people really to introduce hip-hop music to Edmonton and play it on the radio.”

But beyond familial influence, Edmonton itself became a canvas. “I wanted to write songs that were about my actual life and my experiences in Edmonton. The fact that it was so singular and so unique to where I came from was one of the biggest advantages,” he reflects.

Edmonton in the early 2000s was a city with a small, almost invisible hip-hop scene. House shows on rooftops, the indie-rock bands that thrived in local DIY spaces, and the scant but significant underground venues became his classroom. “I started going to people’s house shows, and I was very inspired by a lot of local music in Edmonton at that time. Not even really the rap, but the kind of indie-rock scene,” he says. There was a sense of isolation, but also possibility, and for Pemberton, it became motivation.

Breaking Kayfabe—a wrestling reference to breaking character—was born from that sense of urgency and self-awareness. “It basically means to break character. Like if you’re one of the good guy wrestlers and then you hug somebody who’s supposed to be your enemy. It means you’re pulling the curtains back. That’s what I hoped to do with hip-hop, to show what’s really happening.”

That clarity of purpose is audible across the album, even now. The record’s production, entirely crafted in FL Studio and sequenced in Cool Edit Pro, reveals a young producer experimenting with software in a way that was, at the time, almost unprecedented in Canada. “I was really inspired by artists like Tricky and Prince Paul. I wanted to make music that didn’t sound like anything else,” he says. The resulting tension; the sound of someone testing their limits, of a technical skill stretching toward its horizon, animates every track.

That clarity of purpose is audible across the album, even now. The record’s production, entirely crafted in FL Studio and sequenced in Cool Edit Pro, reveals a young producer experimenting with software in a way that was, at the time, almost unprecedented in Canada. “I was really inspired by artists like Tricky and Prince Paul. I wanted to make music that didn’t sound like anything else,” he says. The resulting tension; the sound of someone testing their limits, of a technical skill stretching toward its horizon, animates every track.

Pemberton’s sound was ahead of its time in part because of the eclectic mix of influences he drew upon. He combined the precision and futurism of electronic music with the lyricism of conscious rap. Freestyle Fellowship, Cannibal Ox, Souls of Mischief, and Del the Funky Homosapien informed his approach to verse, while electronic innovators like Squarepusher and DeFeKT influenced his textures.

Video game music and 1980s pop classics like Falco’s “Rock Me Amadeus” also found their way into the record, making for a sonic collage that challenged expectations. In 2005, when Canadian rap was often defined by mainstream tropes or underground singularity, Breaking Kayfabe felt like a bridge to a new sensibility; intellectual yet kinetic, cerebral yet danceable.

Every track on Breaking Kayfabe captures this duality: deeply rooted in a local milieu while gesturing toward a broader musical future. Songs like “Oliver Square”—now Unity Square, the location’s name changed, the landscape altered—act as time capsules of a particular moment in Edmonton’s history. Listening back, Pemberton admits, is an exercise in reflection: “I don’t recognize the person who made it. I was really cocky when I was a kid. I really went into that record thinking I wanted to take over the world with this abstract underground rap.” Well he did because critical recognition soon followed.

One year after the release of Breaking Kayfabe, Pemberton was nominated for the Polaris Music Prize, placing him alongside Canadian luminaries like Broken Social Scene and Metric. “That was huge for me,” he recalls. “It really springboarded me to a different level, getting played on CBC Radio 3. It catapulted me into a different level for sure.” The album’s success in Canada was in part driven by international attention, a familiar story in a country where local artists often require validation from abroad before being fully embraced at home. “Canadians will always be the last people to appreciate their own artists,” he says bluntly. “We have a national inferiority complex, but that’s a conversation for another time.”

The record’s lasting relevance lies in its boundary-expanding approach. Cadence Weapon brought together electronic textures and rap lyricism in a Canadian context where such synthesis was virtually unheard of. Before him, underground figures like Swollen Members or Buck 65 had charted paths through outsider music or battle rap, but Pemberton took the baton further, creating a sound that was futuristic yet uncompromising.

Twenty years on, Pemberton’s reflection on Breaking Kayfabe is both proud and candid. “It is a good album, and people are going to appreciate it in the future more than maybe you realize,” he tells me, adding a lesson learned over two decades: “You’ve got to chill the f*ck out a little bit and develop a bit of humility. That’ll do you better in the long run.” Humility and self-assuredness coexist in the album itself with each track revealing a young artist navigating his limits, testing his voice, and staking a claim in a musical landscape that was only beginning to recognize him.

The production techniques, once novel, are now instructive. Pemberton’s use of FL Studio and pirated software, his trial-and-error approach to sequencing and sampling, and his audacious recontextualization of sounds—all anticipate methods that would become standard in electronic and rap production alike.

Songs bounce between complex electronic arrangements and raw lyrical intimacy, often in ways that seem effortless but are the product of meticulous craft. This tension between ambition and experimentation, between immediacy and polish, is precisely what makes Breaking Kayfabe endure.

Looking back, the album also functions as a social and cultural document. Edmonton, the city that shaped Pemberton, appears in every track, its quirks and contradictions etched into the lyrics and the textures of the beats. The limited diversity he experienced, the city’s uneven embrace of hip-hop, and the DIY music scene all find their echoes in his songs.

“It just felt like there was nothing happening,” he remembers. “Music was just my catharsis and outlet. I just wanted to do for Edmonton with all the rappers that inspired me what they did for New York and Los Angeles.”

In 2025, Cadence Weapon is, in many ways, the artist he always envisioned being. He has expanded his creative reach into books, new albums, and a multidisciplinary practice that defies simple categorization. “I feel like I have become the artist that I always wanted to be. I’m in the process of writing a book, I’ve got a new album next year,” he says. The trajectory from Breaking Kayfabe to now is a testament to both his vision and his adaptability. While the early tracks brim with youthful bravado and experimental energy, the artist who inhabits 2025 brings reflection, depth, and a broader artistic perspective, and his legacy within Canadian hip-hop and beyond remains substantial.

Breaking Kayfabe Track List:

- Oliver Square

- Sharks

- Grim Fandango

- Black Hand

- 30 Seconds

- Diamond Cutter

- Holy Smoke

- Fathom

- Turning on Your Sign

- Lisa’s Spider

- Vicarious

- Julie Will Jump the Broom