Warning: There is strong language contained in this blog post.

To many radio listeners in Canada throughout the 1950s and ’60s, there was no one more influential than Vancouver DJ Red Robinson, so nicknamed after his trademark red hair. With a single spin of a record, he could instantly turn an unheard-of single into a stratospheric-level hit.

In his 60-odd-years working in radio and TV, he’s done over 3,000 interviews with some of rock ‘n’ roll’s biggest names, including Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Buddy Holly, and Roy Orbison.

Robinson with Buddy Holly in 1956.

Robinson with Buddy Holly in 1956.

Among his many infamous celebrity encounters, he was once told to « Get the fuck off the stage » by John Lennon during the Beatles’ performance in Vancouver in 1964 (a misunderstanding brought on when the Chief Inspector of the Vancouver Police Force, Bud Errington, and the Beatles manager Brian Epstein, asked Robinson to interrupt the show to prevent fans from trampling each other), and once got into an argument about politics with famed Beat poet Allen Ginsberg—and apparently won.

But it is his contribution to introducing Canadian audiences to rock ‘n’ roll that will likely be his most enduring achievement.

In 1953, the then fledgling 16-year-old radio host played the first rock ‘n’ roll record in Canada. It was a single called “Marie” by the Four Tunes, who did an updated doo-wop version of a 1940s original by the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra.

The high schooler had been hanging around a radio show on the now defunct-CJOR, called Theme for Teens, after school. When the show’s original host, Al Jordan, left for good, Robinson took over, regularly playing rhythm and blues and rock ‘n’ roll records before any other radio DJ in Canada.

“There was a little coffee shop not far from the school, called Oakway at Oak and Broadway in Vancouver, that had a jukebox loaded with rhythm and blues songs, like Ruth Brown, LaVern Baker and Lloyd Price,” says the revered radio personality, now 78, over the phone from Vancouver. “When I got my radio show, I thought aha! I’ll take some of this with me, because they didn’t have any of it.”

Ruth Brown’s 1955 song « Mama He Treats Your Daughter Mean. »

Rock ‘n’ roll hit the airwaves in Canada, first in Vancouver, before rippling throughout the country, all thanks to a teenager with a penchant for R&B tunes.

“I would go to the record store to buy a rhythm and blues record and they would hand it to me wrapped in brown paper like it was pornography,” Robinson recalls. “They called it race music. ‘Oh you want some race records?’ they would say.”

In the 1950s, playing a record on the radio by an artist of colour, even in Canada, could provoke a racist response from listeners, Robinson mentions. The birth of rock ‘n’ roll marked not just the emergence of a new era in music; it was a sign of changing attitudes and racial barriers being broken on both sides of the border.

“In Canada, we’re a little smug, » Robinson says. « We think that we didn’t have racial discrimination, but yes we did. Are you kidding me? I put a book out called Backstage Vancouver, and in it there’s a picture of Louis Armstrong sitting with his luggage outside of the Hotel Vancouver because they wouldn’t let him stay there.”

In June of 1956, Bill Haley and His Comets played the first ever live rock show in Canada with Robinson as the emcee at Vancouver’s Pacific Coliseum. Les Vogt and The Prowlers, a local band that had gained prominence playing on CKNW’s radio show the Owl Prowl, opened the legendary gig.

“You could tell the whole world was changing, because the new beat was here,” says Robinson. “That’s the way Bill Haley described it and I agree with him.”

Bill Haley and His Comets’ 1955 hit “Rock Around the Clock.”

The new sound was louder and more dangerous than the big band music that was popular at the time, and seemingly overnight it became the anthem of rebellious teenagers everywhere.

When the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll himself, Elvis Presley, made his first appearance in Vancouver in 1957, Robinson was asked to emcee the show. He says it’s one of the only times that he’s ever been really nervous about introducing an artist.

“You gotta remember something, up until Elvis, no one—not the Sinatras, not the Bing Crosbys—no one rented stadiums,” says Robinson. “That’s how big he was. To stand out there in front of that crowd, and bring out the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, was just unbelievable. The Beatles was an encore compared to what Elvis’ crowd was like. It was just as crazy. Just as nuts. He only did about 22 minutes, and he got the hell out.”

The two bonded backstage, talking about cars, girls, movies and music. “He liked the R&B singers that I liked, people like Roy Hamilton and Jackie Wilson,” says Robinson. “He was a good guy. He was like anyone I had gone to school with. There was no conceit. He had vanity about how he looked, but no conceit. He was more interested in my life than me talking about him.”

Elvis’ appearance in Vancouver in 1957 may have been the most frenzied show to ever come to the city.

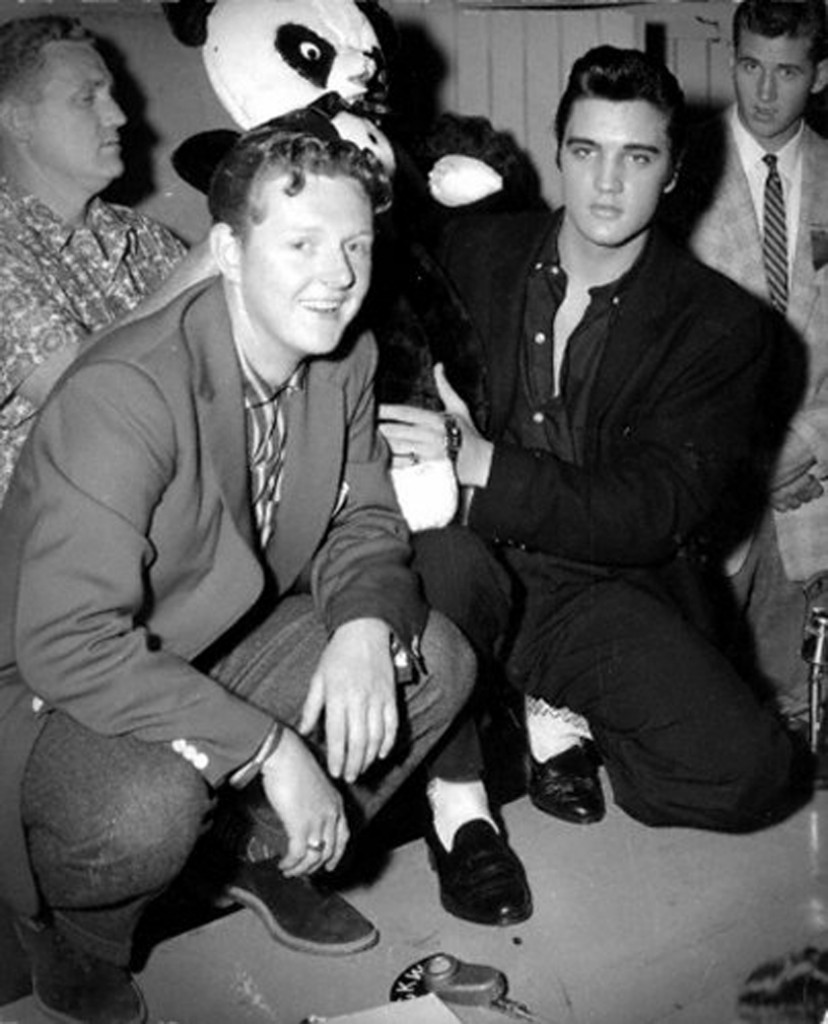

Robinson with the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll in 1957.

Robinson with the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll in 1957.

Inspired by fellow Vancouver DJ Jack Cullen, the far-out host of the Owl Prowl known for his off-the-cuff style, Robinson says: “Up until the time of the disc jockeys, radio announcers were so formal. They would announce it like ‘Ladies and gentleman, heeeeere’s Doris Day or heeeeere’s Glenn Miller.’ But Jack wouldn’t. He was totally ad lib, free form, and I loved it.”

Jack Cullen being interviewed on CBC-TV in 1983.

Taking cues from Cullen, notorious for both his style and crazy on-air antics, such as interviewing people live from a nudist colony or running around town in an Easter Bunny costume, Robinson ushered in his own brand of radio havoc, including an infamous April Fool’s Day prank that told of a whale washing up on a Vancouver shore, which drew over 15,000 people to the beach.

Animal-right’s activists and marine biology students at the University of British Columbia, who assumed that pieces of a whale were being hacked off and made into souvenirs, turned up only to find out that it was all a joke.

“The manager called me in the next morning, and pulls out the Vancouver paper, and it says ‘DJ Brings 15,000 People to the Beach with False Whale Story,’ » says Robinson, who at the time thought the stunt might end his career. “The manager said, ‘Look at that! Look at that! Now tell me what are you going to do tonight to top that?’ I was old enough to understand the signal there was to carry on.”

And carry on he did. With Robinson pulling off all kinds of stunts and breaking out a tidal wave of rock ‘n’ roll records and artists, his hometown of Vancouver became a pioneer for the new sound in Canada.

“Vancouver a trailblazer? Absolutely!” he says. “Toronto didn’t really get going until the ‘60s with artists, like David Clayton-Thomas and Ronnie Hawkins. There was no national exchange in those days between radio stations. We became more north-south, than we did east-west across Canada.”

Following the discovery of Canada’s original rock band, Les Vogt and the Prowlers (who were discovered by Cullen, although he didn’t ordinarily play rock music), a flock of would-be music-makers and rock ‘n’ rollers ensued in Vancouver and across the country.

Robinson is credited for launching the careers of Victoria’s Ian Tyson, who was discovered as part of a radio contest to find the next big rock ‘n’ roll band in B.C., and Thunder Bay-born teen dream Bobby Curtola, whose music broke out big in the U.S. after Robinson sent Curtola’s track “Fortune Teller” to radio stations in Hawaii and Seattle.

« Fortune Teller » by Bobby Curtola became a big hit in the U.S. and Canada thanks to Robinson.

Robinson says his decision to get behind an artist was always instinctual and he believed in asking the audience what to play. He still abides by those rules.

Today, he says he loves singers, like Adele and the late Amy Winehouse, and CanRockers, such as April Wine and Rush, and despite a (sort of) retirement from radio in 2000, he continues to host one radio show a week on CISL in Vancouver from noon to 4 p.m. on Sundays, where his playlists can include anyone from Bruce Springsteen to (of course) Elvis Presley.

“I’ve had five retirement parties,” he admits.

Having spent over six decades working in radio, Robinson says “consistency and an ability to be able to adapt to the times” has been the key to his success.

“But the year of the disc jockey is almost over,” he says, before referring to Tom Petty’s song « The Last DJ » as a reflection of his current thoughts on radio. “(Commercial) radio’s so cookie-cutter today.”

“There goes the last DJ/Who plays what he wants to play /And says what he wants to say…and the boys upstairs just don’t understand anymore, » Robinson says, reciting the lyrics of the song.

In 1995, Robinson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland at its opening, and is among only three Canadians to ever be recognized by the institution—radio DJs Dave Marsden and the late « Jungle » Jay Nelson are the other honourees to be included.

“I guess we had an influence on rock ‘n’ roll in Canada,” he says with a laugh.

– Julijana Capone